In my eyes, my father has always been a calm observer. If in another time and space in the universe, he saw me writing this article, he would definitely roll his eyes and would probably say, “Boring” as he was a man of few words. Being an introvert, he rarely spoke about himself or his youth for that matter, and writing this article today is a challenge in itself.

In 1931, he was born in the old house of our ancestors in Kunming, Yunnan which was located in the middle of Changchun Road, on a lane called Quanxue. The traditional layout of the house followed the “one imprint” pattern which included: the main house with adjacent rooms on the east and west sides with tiled roofs, wooden structures, and carved windows There was also a central courtyard.

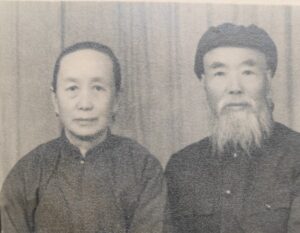

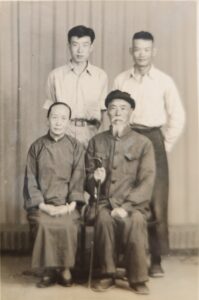

His dad, and my grandfather, was a geological surveyor which was quit a rare profession in those days. Before being with my grandmother, he had previously been married with a spouse that gave him three sons which became half-brothers to my dad. As an only child from that union, my dad never really spoke about his parents and I never got a chance to meet them.

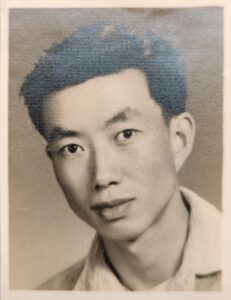

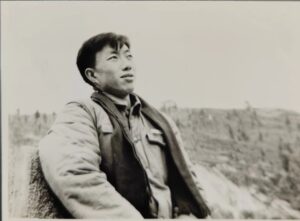

According to a distant cousin, my father had joined the underground party during the student movement in early 1949, where he was a song director. As tensions rose between the Nationalists and Communists, and things got worse, he eventually left without saying anything to join the Border Defense (Red Army’s Guizhou-Yunnan-Guangxi Border Defense Detachment) to engage in armed combat. Still today,it’s baffling for me to conceive how someone as gentle and soft as himself could adjust to the harsh life of guerrilla warfare. Regardless, he eventually returned home to his parents.

4o

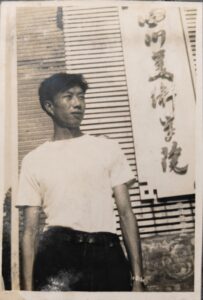

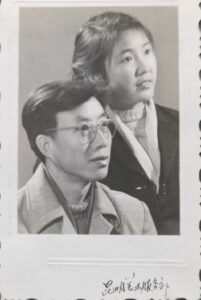

During those chaotic times and after his return, my grandmother naturally worried about his safety and even went as far as locking him in his room to prevent him from going out, fearing for his life. Because of this, he was forced to desist from the party. Later near the end of 1949,when things settled down, and the situation returned to a somewhat normal state, his former comrades vouched for him, and he rejoined the Communist Party. My father, known for his singing skills, joined the military’s music division but after a short while left the army, having being assigned to work in a cultural unit under Chengdu’s municipal government. Later, he followed the call of his heart and determinedly decided to return to academia. Thus, in 1955, he took the entry exam for the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute as his ultimate happiness was in painting. It was at that time that he became a student and protégé of Mr. Li Youxing.

As a young adult, my father spent most of his time away from home, leaving his parents to tend to themselves. Mom told me that one morning, grandma went out to empty the chamber pot (a term used for a bedpan in those days when houses lacked bathrooms), she collapsed on the roadside, and passed away abruptly. My granddad unable to withstand the loss, soon followed. The suddenness of the events led my eldest uncle to come from the countryside to administer both grandparents’ funerals as my father was unable to tend to family affairs because he was at the Art Institute. Although it shouldn’t have been too difficult for him to travel from Chongqing to Kunming, I can only speculate that something significant happened, preventing him from returning. The consequences of this situation were devastating for him and can possibly explain his unconscienced capacity to tend to the estate.

After their passing, strangers occupied my grandparents’ old house. So, although I was born in Kunming, I did not grow up in that ancestral home but in a small house on Huashan South Road. Our unit was less than ten square meters, without a kitchen which meant we had to cook with our neighbors in the hallway. Despite the cramped living conditions, my childhood memories are filled with happiness, as my father showered me with his love. The first thing he did after work every day upon my return from school was to lift me up high in the air and spin me around. Our laughter resonated and the conversations we had lit up my entire childhood with bliss.

To reclaim my father’s ancestral home, my mother, through a mutual acquaintance, found a military representative from another province who needed a living place for his family of 5. Thus, an agreement was made for him to use his military influence to evict the people occupying my father’s ancestral home, where both families moved in. My uncles also helped a lot in this matter. Finally, we regained possession of the ancestral home.

In the beginning, everything was fine, the atmosphere was lively with the other family’s dog and chickens. Life was much better than before, and my mom’s singing resonated both inside and outside the house. Unfortunately, the good times didn’t last because two families living under the same roof became more complicated. The other family who had military connections, used this to their advantage and revealed their true colors. They bullied my mom, labeling her as a rightist, and tensions grew between both families. Despite our efforts, they refused to move out and they were determined to govern the home.

Fortunately, my dad had a friend who was also an artist who was willing to exchange his small house for ours and deal with the military representative and his family. Once again, we moved away from our ancestral home, settling on Justice Road of all names. We lived on the second floor, while the ground floor housed a storefront dedicated to charcoal portraits, that had long disappeared from its glory days as a prominent rendezvous for the artistic community.

That tiny house on Justice Road was filled with past memories of local Kunming artists who often gathered at our home for meetings. I vividly remember a white-haired teacher by the name of Sun Yunling, who smoked so much that the room was one great cloud. My dad’s painter friends Yuan Xiaocen, Zhu Bing and Xia Shenglan, the museum curator Yang Tianyou, and, of course, my parents’ mentor, Mr. Li Youxing and his wife, along with various other strong opinionated artists indulged in discussions on art and other various topics.

One of my fondest memories is of my father painting movie banners. Before the late ’80s and early ’90s, Billboard size movie insignias were entirely hand-painted. My father had a large studio at the Kunming Theater, where I spent a lot of time. Once, he was working on a piece for an industrial movie. Mr. Feng, who helped us move houses, joined in. After days of hard work, when they reached the part depicting the intense flames of molten iron in a steelmaking scene, Mr. Feng said, “Let the little sister do it” (everyone used to call me little sister). Dad lifted me onto his shoulders, Mr. Feng handed me the paint brush, and with all my might, I threw colors onto the movie portrait. I was ecstatic and at the same time surprised, asking daddy why I was allowed to mess around with their work. Dad said that details serve the overall picture, as long as the general direction was respected, He underlined that small imperfections would not affect the overall picture. The end result of my dad’s work would be displayed on buildings in Dongfeng Square and Qingnian Intersection for the entire city to see. I felt particularly proud.

In 1979, my mother finally returned to her job after a period of forced rehabilitation (see her memoire). My father was also transferred back to the Institute of Arts and Crafts. He was dissatisfied with the lackluster attitude of people in state-owned enterprises, so he actively contacted his old classmate, Ms. Sun Yunling, who was working at Yunnan Arts Institute. At that time, the institute was planning a new major in dyeing and weaving, and the opportunity was just right.

By 1985, the ancestral home had become unsafe for dwelling, and the military representative who had been asserting his authority finally moved out. My mother, however, never wanted to talk about this incident ever again. Soon after, one of my uncles contacted a prison warden from another province who could provide the funding while to. rebuilt the house together for both families, each owning half as the land belonged to us.

Everything settled down, life improved and in 1986 my father finally transferred back to the Yunnan Arts Institute as a professor.

After graduating from university in 1991, I went through a restless and rebellious period when someone encouraged me to focus my energy on starting a business. Without my parents’ knowledge, I remortgaged the newly built house and secretly took a loan from the bank with which I used to start my decorating company. This marked the beginning of a challenging and profound adventure into entrepreneurship. Around that same time, the Chinese government initiated massive urban expropriations for its own benefit. One morning, I woke up to find the word “Demolition” painted across our front door. We were given two months to move out and find new accommodations either with relatives or friends. The 1990s were a disaster in China with widespread urban expropriations. Once again, our family’s stability was threatened by a turn of karmic events. I remember a specific moment, watching an elderly person die alone in the ruins of his home that had been demolished. It was at that precise time that I started contemplating the idea of leaving China for a better life.

Aa a young adult, my father consistently encouraged and supported my quest for freedom, even if that meant pursuing my dreams elsewhere. A few years later, upon completing of my company’s only project, I decided to sell the business and transitioned into becoming a tour guide. This gave me the means.. to discover the world outside what I had already known and learn more about myself. Concurrently, my perpetual thirst for learning and growing lead me to learn the French language, preparing me for future opportunities.

My father was an atheist, and during my childhood, I was fond of Taoism, embracing the joy of the present moment. As I grew older, my interests shifted towards Buddhism, more specifically Tibetan Buddhism. Our home was filled with a vast collection of books, and at every possible occasion, my father would gift me with books. I vividly remember “Travels with My Aunt,” “Love Stories,” “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,” and other novels, essays, and poetry that became my cherished companions.

I developed a strong affinity for the I Ching and fortune-telling, a fascination my father would likely dismiss as “boring” if he knew. In my early years, I accompanied my father in collecting various dyed and woven items from Yunnan’s ethnic minorities. Together, we traversed villages, witnessing villagers using natural dyes and traditional weaving techniques. In the 1990s, my father established a Dai brocade weaving factory, combining machine and manual weaving to preserve the traditional crafts of Yunnan’s aboriginal minorities.

In a collaborative effort between my father and my decorating company, we crafted a one-ton copper gong for a picturesque village in the Hainan Island during the early years of my adulthood. This unique project created a cherished memory as father and daughter worked hand in hand to contribute to the preservation of a cultural heritage for the region.

After my departure from China in 2004, my parents enjoyed a period of rare tranquility and happiness. Though their children were far away, they no longer had to worry. In his later years, my father seemed to rejuvenate through his artistic vitality. He unexpectedly created more than 200 oil paintings. This both surprised and delighted me, but I innerstood that father cherished his solitary time with his true one love; painting.

After a lifetime of being busy with family responsibilities, he finally had carefree moments in his 70s, living like a child with his canvases, brushes, and an electric scooter that he changed every few years.

In my eyes, my father was broad-minded and wise. He believed that art came primarily from insight, and indoctrinating others with a specific vision was futile. Evidently, he never insisted on teaching me how to paint. His approach to art was his approach to life which was,do not run towards a result, let it find you. This simple attitude combined with his gentle nature, allowed him to navigate through various situations unscathed. Compared to my mother, his life was much smoother then her’s. In the end, I believe my father hoped that I would inherit these qualities. He always reminded me to consider things thoroughly, avoiding situations where the beginning and end couldn’t align. This has indeed been my weakness, as I often give my all in everything, I do but struggle to stay calm in the final moments. What is called “ruining previous efforts at the final step” perfectly describes me. This is something I always keep in mind.

After my parents passed in 2023, I became an orphan and thus finally a fullfledged adult. I concluded that life was short, and every moment of every day was precious. I now understand that the departure of our loved ones is just a transition of their presence from material to energy. Their departure also marked the end of my 20 years of living away from home, physically and emotionally, as my parents are now my everpresent light guardians.

This pain is not unique to me but shared by many Chinese living in foreign lands, who often long for their families back home. The familiar dialect over the phone is comforting, but watching them age gradually is heartbreaking.

Looking at the hundreds of artworks my father created, I realize that each unique piece reflects his deep love for life and his profound apprehension of the freedom he has always yearned for..

Now that these works have travelled across half the globe to Canada, I cherish ever single one like a timeless memory piece of recorded the shared experiences and emotions of my Dad.

They are a precious heritage of our family, embodying the spirit of a timeless era and connecting us through the emotional bonds of our bloodline.

Sharing my father’s art with a broader audience is destined to be my life mission, and I believe that the works of my father will open a window for the world to see the struggles and hardships of Chinese artists from the 1950s. Living in such a tumultuous era, their expression of freedom and love for art remains unwavering. The years await, and the future is promising.