by: Ni Wang 2023. 11 .25

Preface

In 2024, hundreds of paintings found their way to North America, settling quietly in a foreign land. These artworks tell the story of a family’s rise and fall, as well as a half-century of love and dedication.

The story begins in 1936 in the southwestern part of China, during the turbulent times of the Anti-Japanese War. In Kunming, Yunnan, a prominent family welcomed the birth of a baby girl named Zhou. Thirteen years later, with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the family’s glory began to fade, but Zhou’s fate was rekindled by art. She entered the Southwest Academy of Art to study painting and met her other half there. Despite a lifetime of hardships, they never wavered in their passion for art, leaving behind hundreds of touching works.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, the couple passed away, and their precious paintings were brought to Canada by their daughter. This marked the first time these artworks entered the world’s sight, quietly narrating a bygone era and a life of passionate dedication to art.

Title 1: Traces of Time

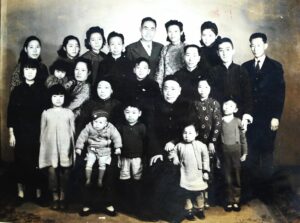

In April of the lunar year 1936, Kunming’s spring was exceptionally pleasant. Willows swayed gracefully, and vibrant flowers bloomed, enveloping the entire city in the gentle breeze of spring. On the lively Zhengyi Road stood a pharmacy named Zhenhua, thriving with business. My grandfather, Zhou Xiaoyun, was the owner—a skilled pharmacist. On this particular day, his thoughts were preoccupied with a significant event—the arrival of a new life in the family.

“The street scenes of Kunming in the 1940s, influenced by the construction of the Sino-Vietnamese Railway by the French, turned this small city in southwestern China into the most ‘Westernized’ and bustling provincial capital. Photo by H. Allen Larsen.”

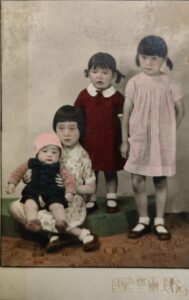

According to the family genealogy, it was the “Hua” generation’s turn for the Zhou family’s girls. The eldest daughter was named Zhou Yuehua, the second Zhou Yuhua. As fate would have it, the third child was also a girl. Great-grandfather Zhou Yunsheng chose the character “Bao” for her name, naming her Zhou Baohua. “Bao” symbolized precious and rare things, gathering the essence of heaven and earth. “Baohua, Baohua,” echoing the treasures of nature, conveying the family’s precious affection for this newborn life. This baby girl was my mother.

In those times, despite Kunming’s signs of prosperity, the shadow of the Anti-Japanese War loomed. Zhenhua Pharmacy actively participated in fundraising campaigns led by organizations like the Kunming Chamber of Commerce. Faced with the ravages of war, the Zhou family pharmacy readily extended a helping hand. The echoes of war had not yet dissipated, and the Kunming City Archives preserved the historical traces of those times. Receipts recorded generous donations from Zhenhua Pharmacy and other businesses, reflecting the historical responsibility of the Zhou family and witnessing the united efforts of the people of Kunming during challenging times.

Zhou Baohua spent a happy and warm childhood within Zhenhua Pharmacy. Great-grandfather Zhou Yunsheng, an art enthusiast who collected calligraphy, paintings, and ceramics, introduced the beauty of art into her life. In the nurturing family atmosphere, Zhou Baohua, from a young age, displayed a strong interest in art. She enjoyed observing the dance of willow trees and the enchanting beauty of peach blossoms in the garden. Great-grandfather Zhou Yunsheng encouraged her to experience life wholeheartedly and express her inner cultivation through art.

A few years later, her younger sister Zhou Manhua and fifth brother Zhou Runsheng were born, bringing more vitality to the family. The birth of a boy, my uncle, brought immense relief to my grandmother Liu Yaying. In 1940s China, having a son (male heir) was crucial for the continuity of a large family. His arrival filled the entire family with joy and laughter, instilling hope in the successive generations of Zhenhua Pharmacy.

At the age of 13, Zhou Baohua graduated from junior high school, and her teacher gave her the name “Luna,” symbolizing versatility and charm like Lu Xun. It was a period of happiness for my mother, but little did anyone anticipate the unfolding of a great tragedy.

Title 2: Decline of Zhenhua Pharmacy

In 1949, Kunming was peacefully liberated. In the early days of liberation, as per the Land Reform Law of the People’s Republic of China, the land of landlords and surplus houses in rural areas were confiscated. The Zhou family was categorized as a local wealthy asset owner and landlord. Zhenhua Pharmacy, as part of the family assets, was entirely confiscated by the new government, and the storefront was later sold to an international photography studio (which still exists today). Great-grandfather Zhou Yunsheng, the pillar of the family and owner of Zhenhua Pharmacy, and the president of the Kunming Chamber of Commerce, saw everything stripped away overnight. Due to political reasons, he was recommended to work at a distant place, and his profession as a pharmacist was downgraded to a salesperson at a medicinal material company. Great-grandfather and great-grandmother, already of old age, could not bear this blow, and they passed away one after another. In just three years, the grand Zhou family legacy built over generations crumbled. After dealing with the funeral arrangements for great-grandfather and great-grandmother, the family’s fortunes took a downturn.

Three years later, my mother graduated from middle school. She had to join her elder sister in supporting the family’s livelihood and found a position in the library of Puer Middle School.

Title 3: Mother’s Artistic Journey

At the age of 16, my mother became the librarian at Puer Middle School, a decision made to help support her grandmother. Meanwhile, her elder sister and second sister were arranged to marry into good families, making my mother’s marital status a topic of discussion among outsiders. Following the family’s conventional path, after her elder and second sisters got married, my grandmother started worrying about my mother’s marriage. A neighbor suggested that his son, who had just returned from the Korean War as a victorious soldier, was interested in my mother. My grandmother informed my mother about this, saying that the neighbor’s son wanted to invite her to Cuihu Park. My mother reacted strongly, loudly exclaiming, “Doesn’t he look in the mirror? Are we a suitable match?” Her voice was so loud that even the neighbors outside might have heard. From then on, that family never dared to bring up the matter again, and my mother, like the wind, moved freely, with neighbors gossiping about her, and no more suitors came knocking on the door.

Unwilling to be a pawn manipulated by others, my mother embarked on a journey of self-study. Fueled by her passion for art and desire for freedom, she diligently improved her painting skills. In 1954, she successfully enrolled at the Southwest School of Fine Arts, later known as the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, becoming a student of the Eastern color master Li Youxing.

In that moment, I imagine my mother as a free bird, soaring in her own sky. This experience became a turning point in her life. With her efforts and courage, she proved that a woman could independently choose her future and pursue her dreams.

At the Southwest School of Fine Arts, my mother began a new life. In this temple of art, she pursued her inner passion—painting. Every day, she wholeheartedly devoted herself, using brushes to express her emotions and inspiration.

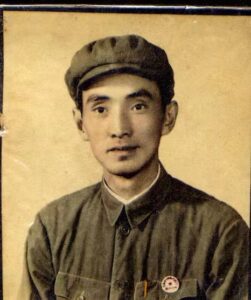

Accompanying her on the exploration of the artistic realm was a like-minded fellow student named Wang Qingming. They shared a deep connection and became intimate confidants. While Wang Qingming exuded the charm of a gifted artist, my mother was as beautiful as a flower. They immersed themselves in the spring of youth, unaware that a storm was about to descend. In the spring of 1958, the political winds of the Anti-Rightist Movement raged, intensifying ideological conflicts on campus. Wang Qingming, as a student uninterested in political struggles, preferred to focus on artistic creation. However, fate relentlessly entangled him in this maelstrom. In a heartless era where human nature succumbed to political fervor, he was branded a rightist and swiftly became a sacrificial pawn in the political struggle. His ideals and talents were ruthlessly crushed. My mother, disregarding her own safety, boldly spoke up for her good friend, expressing clear sympathy. In stark contrast to the prevalent self-preservation during those times, her upright and brave stance came at a heavy cost. She, too, was labeled a rightist, isolated, and eventually forced to leave the school. My mother couldn’t complete her studies and, filled with sorrow and indignation, packed her bags and returned to Kunming.

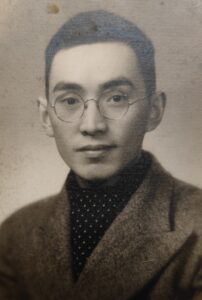

During the days of my mother’s humiliation, possibly long before that, there was a junior from a lower grade who had been paying attention to her. When my mother sadly left the school, no one came to bid her farewell except that junior. He accompanied my mother, helped her carry her luggage, and spoke many comforting words. He consoled my mother, asking her to rest well at home and wait for his letters. Together, they walked from the school to the station. It was such a heart-wrenching journey! Yet, even in the midst of great adversity, my mother found a glimmer of light in the eyes of that junior. That junior was my father, Wang Bangsi. At that time, Wang Qingming, the talented artist, was struggling for his own survival, unable to consider my mother’s shame.

Title 4: Work and Marriage

In 1958, my mother returned to Kunming to find her family in disarray. Grandfather Zhou Xiaoyun, due to the family background, had faced repercussions in every political movement. He worked as a pharmacist and was engaged in drug testing. Originally working well at the Provincial Drug Testing Institute, he was unexpectedly recommended to join the Kunming Medicinal Materials Company under the pretext of supporting frontier construction. He went from being a pharmacist to a medicinal materials salesperson. My grandmother, left alone with several children in Kunming, lived in a small alley in Dongsi Street. After the passing of great-grandfather and great-grandmother, two more younger brothers joined the family. According to the family genealogy, the second younger brother was named Zhou Dingsheng, and the youngest Zhou Jiansheng. Life was difficult for my grandmother, relying on handcrafting paper folding and pasting tea bags for a livelihood. Ignoring the objections of her elder sister, my mother, and through the connections of the neighborhood committee, began to look for work opportunities.

A few days after my mother returned home, she received a letter from my father, marking the beginning of their romantic correspondence. Every time my mother replied, she personally went to the telegraph building to send the letter, claiming that it could calculate the number of days it would take for my father to receive the letter. All the stamps used in their correspondence were commemorative stamps. My second uncle, with a hobby in stamp collecting, mainly collected the stamps they used. Even today, the stamps on the envelopes bear witness to the sweet days of their courtship.

My grandmother, through the community’s connections, secured a job for my mother. She became a worker at the Yunnan Printing and Dyeing Factory (later transferred to the Pattern Design Department due to her artistic talents). My mother began working for a living, opening the door to her creative journey.

Two years later, my father graduated from Sichuan Fine Arts Institute and was assigned to teach at the Guangxi Arts Institute.

During this period, every holiday, my father would take a bus to Kunming to see my mother. Each time, he brought a bag full of Guangxi Shatian pomelos. In Kunming, my father also enjoyed taking my mother and my uncle to a dessert shop on Wu Yi Road to eat “Four Happiness Tangyuan.” My uncle said that during those times, my father laughed the most joyfully. In my father’s works, a substantial number of sketches and paintings of the Li River, Yangshuo, and Guilin are attributed to that period. My parents enjoyed a rare period of tranquility, exchanging letters, meeting, parting, and anticipating the next reunion. They were deeply in love, like the beautiful glow of the sunset.

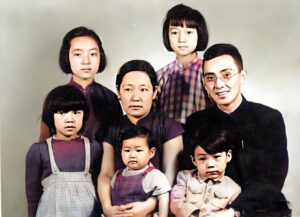

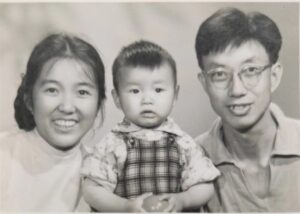

In 1963, my mother gifted my father a beautiful photo and announced her lifetime commitment to her family. My grandmother and siblings were overjoyed. At last, with the breaking dawn, my parents were married. My father was also transferred from Guangxi to Kunming.

In 1964, their first love blossom arrived—their son, my elder brother. Initially named Zhou Qun, it was later changed to Zhou Peng, sounding similar to “Qing” (clear), meaning the sky had cleared. My eldest uncle suggested that for a boy, he should aim high, so they changed it to Zhou Peng.

Chapter 5: Armed Struggle and Political Turmoil

1966, the horn of the Cultural Revolution sounded, and simple, peaceful lives were once again plunged into difficult circumstances. My mother, just starting her job at the factory, faced challenges in the tumultuous era.

In the printing and dyeing factory, my mother initially worked in the printing workshop, which operated in three shifts. New workers usually started with the night shift, but due to her living situation, the factory leadership made an exception, allowing her to avoid the night shift. However, her talents quickly got her transferred to the pattern design department, causing dissatisfaction among some night shift workers, led by someone named Wang Qi.

In that turbulent era, jealousy grew like poisonous snakes. Wrapped in the guise of political righteousness, Wang Qi patiently observed, his jealousy burning like a fierce fire. He silently waited for an opportunity, and the Cultural Revolution provided him with a legitimate reason. Due to my mother’s birth into a formerly wealthy family, she became a target of the revolution once again.

One evening, Wang Qi, accompanied by an armed struggle team, arrived at my grandmother’s house to arrest my mother. Unfortunately, she wasn’t there that day, and they pressured my grandmother to provide information. Helpless, my grandmother allowed my uncle to lead them to the designated location. As night fell, the armed struggle team called out loudly from downstairs, demanding my mother to come down. Wang Qi, with a group of people, went upstairs and forcefully dragged my mother down, shoving her into a truck, and swiftly departed.

Days later, my mother returned to my grandmother’s house. As she removed her sleeves, her right hand was covered in purple bruises, and her arm was severely swollen and deformed. My mother’s right hand was permanently disabled. Despite this, she persevered and continued her artistic journey with her left hand.

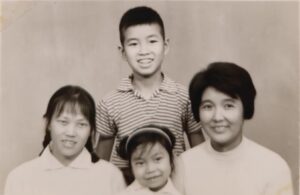

In the late 1960s, my mother’s artworks were all created using her left hand. Each piece reflected an unyielding artistic soul that couldn’t be stripped away. In those years of dark clouds looming, my mother gave birth to her second child (myself). She named me Wang Ni, meaning my little sister, and my birth brought her the courage to survive.

However, after losing the ability to work due to her right hand’s disability, my mother faced another setback. She was sent to the countryside for “re-education” and had to abandon her artistic pursuits. Accompanied by my elder brother and me, she embarked on a challenging journey into the unknown, performing physically demanding labor.

Chapter 6: My Childhood

Growing up, my memories of my mother were filled with her beauty and cleanliness. Regardless of how humble our living quarters were, she turned them into warm and orderly homes with her hands. During the years when my mother didn’t have a job, my father single-handedly supported our family. His work at the Kunming Theater, with a monthly salary of 20 RMB (equivalent to 4 USD), involved creating movie advertisements and maintaining the screening hall.

I remember my father’s sketchbook from that period, documenting our lives during those challenging times. My mother, with her artistic spirit, continued to create even after losing the ability to use her right hand. In the early 1970s, I was born, bringing more joy to the family. Our family’s financial situation was modest, and my mother helped my grandmother paste tea bags for extra income.

Chapter 7: A New Beginning

In 1977, the nightmare of the Cultural Revolution finally passed, and my mother was officially exonerated. By then, our family had moved to Dongjiawan, bringing new hope. My father also returned to the Institute of Arts and Crafts. The previously unemployed decade seemed like a distant dream, and my mother received a compensation of 1000 RMB (about 139 USD), a significant sum at that time. The entire family was jubilant, and this joy lasted for a long time.

Later, my parents bought a Sony tape recorder from Japan, becoming a valuable possession in our home. My father, dedicating himself to learning English, listened to BBC broadcasts, and that tape recorder witnessed many good times. My mother, working tirelessly, eventually became the Chief Senior Arts and Crafts Designer at Yunnan Printing and Dyeing Factory. During this period, she represented the factory at exhibitions across China, leaving footprints in various cities.

Chapter 8: Enjoying Golden Years

In 2004, after my departure from China, my parents leaned on each other and enjoyed happy years together. My mother enrolled in a nearby senior university, where she made friends with like-minded individuals, sharing life stories and wisdom. Her love for literature deepened, and she finally had time to savor “Dream of the Red Chamber” while diligently studying calligraphy.

Besides studying, my mother has created a small rooftop garden at home, where various flowers bloom under the sunlight. Every morning, she diligently waters and trims them, caring for them with great love. In one corner of the garden, my father has an art studio. I often imagine my parents in that small world, one immersed in painting while the other tends to the flowers. Occasionally, they exchange a few words, silently enjoying beautiful moments under the azure sky of Kunming, fulfilling the promise of “holding hands and growing old together.”

They also adopted a little cat, becoming a comforting presence in my mother’s life, bringing warmth to their days.

Influenced by me, my mother started to explore Buddhism. Every night, she would play recordings of Buddhist scriptures and chants, finding inner peace and solace in the melodies of Buddhist music.

My mother has always been strong and formidable. During a family gathering, she once said that no matter what, my father had to live until 93, and then he could be at ease. She wanted him to accompany her, and I remember hearing this, turning to my older cousin with a smile, saying, “Is my mom a deity, managing everything from heaven to earth and even determining my dad’s lifespan?” Unexpectedly, my mother’s words became reality. After contracting COVID-19, she passed away a week later at the age of 86, and my father followed three months later, reaching the age of 93.

My greatest regret is not being able to be by my mother’s side when she passed away. I owe her a final farewell. One night, I had a dream, and I turned that dream into a poem, serving as the conclusion to this memoir. I may have missed many nights and days in my mother’s later years, and I cannot make up for it. However, I will cherish each of her paintings throughout my life, just as she cherished her children. My mother’s wisdom made me understand that the essence of art is love, and the ultimate state of art is sharing.

Order doesn’t suit me well

I excel in wild speculations

How to achieve those unfulfilled dreams

Owing my mom a farewell

One night, I dreamt of coming home

Parents pampering me

Then, the departure was near

Parents busy helping me pack

Mother took me to a restaurant

Ordered a chicken

Gently looked at me

Thinking, I don’t like eating much before a flight

In the end, mother and daughter hugged

Saying, unsure if the next meeting Will ever happen

Tears merging together… It was a beautiful farewell

Completed in another dimension

Unable to occur in This lifetime

The Buddha says

Form is emptiness

Emptiness is form…

With this lengthy piece, I commemorate my mother, Zhou Baohua.